Clinical Summary[edit]

This 68-year-old white male had a local excision of a pigmented lesion (melanoma) on the skin of his back. Three years later he became aware of a "lump" in his left axilla. Examination confirmed the presence of a 2.3-cm nodular lesion. Subsequently, the patient underwent a surgical procedure for removal of axillary lymph nodes.

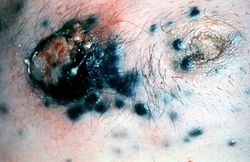

This is a gross photograph of skin with melanoma. Note the black pigment, multiple satellite nodules, and focal ulceration. Some of the satellite nodules affect the nipple.

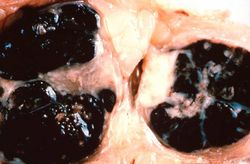

This is a gross photograph of lymph nodes almost entirely replaced by black pigment (melanin).

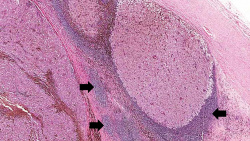

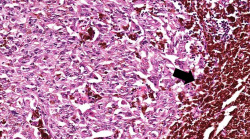

This is a low-power photomicrograph of lymph node that is almost completely replaced/filled with tumor. This lymph node has a capsule (1) and some remaining lymphocytes (2) but the remainder of the node is replaced by tumor cells.

This higher-power photomicrograph shows the remaining portion of lymph node (arrow). The rest of the lymph node is invaded by a neoplasm composed of cells with lighter eosinophilic cytoplasm and pigment.

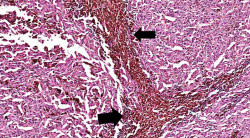

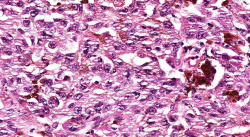

This is a higher-magnification showing the abundant extracellular melanin (arrows) surrounding the tumor cells. This section of neoplasm shows the numerous cells with abundant cytoplasm and brown pigment within the cytoplasm of some of these cells.

This is a higher magnification showing the abundant extracellular melanin surrounding the tumor cells (brown pigment).

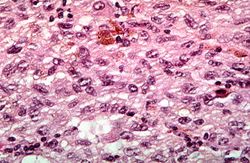

This is a high-power photomicrograph of the main tumor mass with the cells growing as poorly formed nests and sheets of cells. There is little if any pigment in this section.

This is a high-power photomicrograph of the main tumor mass showing the cellular details. The individual melanoma cells contain large nuclei with irregular contours having chromatin clumped at the periphery of the nuclear membrane and prominent red (eosinophilic) nucleoli.

Virtual Microscopy[edit]

Study Question[edit]

Most melanomas arise in the skin; however, other sites of origin include the oral and anogenital mucosal surfaces, esophagus, meninges, and the eye.

Sunlight appears to play an important role in the development of skin malignant melanoma. Lightly pigmented individuals are at higher risk for the development of melanoma than darkly pigmented individuals. Sunlight does not seem to be the only predisposing factor, and the presence of a pre-existing nevus (e.g., a dysplastic nevus), hereditary factors, or even exposure to certain carcinogens may play a role in lesion development and evolution.

Approximately 40% of human melanomas express a tumor specific antigen referred to as melanoma antigen-1 (MAGE-1). Molecular analysis has revealed that the gene encoding MAGE-1 is present in normal cells as well as in tumor cells, and there is no evidence that it is mutated in cancer cells. However, as has been seen in some animal tumors, the gene is silent in normal adult cells; whether or not it is expressed during development remains to be determined. CD8+ cytotoxic T cells specific for MAGE-1 can be obtained by culturing tumor cells with patients’ lymphocytes in vitro.

Additional Resources[edit]

Reference[edit]

Journal Articles[edit]

- Banerjee SS, Harris M. Morphological and immunophenotypic variations in malignant melanoma. Histopathology 2000 May;36(5):387-402.

- Shain AH, Yeh I, Kovalyshyn I, Sriharan A, Talevich E, Gagnon A, Dummer R, North J, Pincus L, Ruben B, Rickaby W, D’Arrigo C, Robson A, and Bastian BC.The Genetic Evolution of Melanoma from Precursor Lesions. New England Journal of Medicine 2015 Nov;373:1926-1936.